The Renaissance man in a Vinnie’s suit

Canberra, ACT

Tim Hollo and Andrew Braddock, ACT Legislative Assembly Member for Yerrabi, at the Conservation Council Forum

On a beautiful autumn day in April, Tim Hollo, candidate for the Federal seat of Canberra, spoke to a sea of green at his campaign launch event in Glebe Park. Just minutes before, Prime Minister Scott Morrison had announced that Australia would go to the polls on May 21.

Morrison is often criticised for his “absence”. That day in the park, some in the audience mocked his timing. Was Morrison’s “presence” at Government House, and his election announcement that morning, coincidental, or was it designed to divert media attention from the crowd gathered for the launch of the ACT Greens’ federal election campaign?

Coincidence or not, Hollo capitalised on Morrison’s moment with a spirited battle cry for the ACT Greens: “41 days and counting!”

Hollo’s promise to “shake-up politics” was enticing. The crowd met his words with enthusiastic cheers of “shame” whenever he highlighted yet another failure of the Morrison Government.

Hollo asks his audience: “Are you ready for an inspiring, positive vision for the future … a politics we can actually trust … a politics that puts people and planet first, instead of private profits … a fair society?”

Committed to democracy

Hollo is committed to stopping “the richer getting richer, the poor getting poorer”. He believes passionately in democracy. “Our communities and democracy work best when we all take part, when every voice is heard”, not when “the people are told to ‘bugger off’ for the three years in between elections.”

While Hollo did not win a seat in the House of Representatives in his first run at Federal Parliament in 2019, he did achieve an impressive number of votes and a respectable swing of +4.59% to The Greens in what has traditionally been a safe Labor seat.

A punishing schedule

Since 2019, Hollo has shed the vestiges of his “last hippy, long hair, rainbow knit look”, for a more contemporary (though not-quite-yet-hipster) image. He has also continued to campaign relentlessly, reflecting the commitment he made to grass roots community engagement and consultation when running in 2019.

Andrew Braddock, ACT Greens Member for Yerrabi, who has known Hollo for around five years, says Hollo is a “passionate advocate of community and how the community can work together to solve its problems, whether they be global-scaled climate change issues, down to very local, individual issues”.

“What impresses me is that he does things at the community level,” he says. “Tim has worked with local community on local plantings and is very much in touch with the community. This is not something you usually see with people who have big ideas, but Tim is very much down on the ground making those things happen.”

On any day (or night) you’ll find Hollo working at campaign stalls all over Canberra, door knocking or talking to people outside their workplaces, in Garema Place in the heart of the city, at aged care homes, at suburban shopping centres, at residents’ association meetings, and at evening events such as the University of Canberra Nursing Society Ball.

Braddock says that during the time he has known him, Hollo has “devoted all his time to support his values, to run as a candidate”. “His work with the Green Institute, a progressive think tank generating ideas and debate on progressive issues, has been his baby,” he says. Braddock is not sure if Hollo conceived of the Green Institute “but it has been his passion and his work for a long time”.

Hollo seems keen to listen to as many people from across Canberra as he can, and to share with them The Greens’ vision and policies for positive change in Australia. Even a brush with COVID in late April didn’t keep Hollo down for long. He was back on the campaign trail by 30 April.

Shifting the Culture of Consumption

On 28 April, at a Conservation Council forum for six ACT Federal Election candidates at the White Eagle Polish Club in Turner, Hollo was a picture of sartorial elegance in his “$40 suit from Vinnies”.

It was Hollo’s sixth campaign gig that day.

Hollo’s choice of wardrobe, putting his money where his mouth is, highlights both his integrity and a lifelong commitment to the environment, fostered as young child by English broadcaster, biologist, and naturalist, David Attenborough. With Attenborough as his childhood superhero, it is no surprise that, as an adult, Hollo claims to have “cut his teeth as an environmental campaigner.”

In 2011, Senator Christine Milne, Deputy Leader of the Australian Greens, thanked Hollo (and others) in her office for six years of policy rigour in support of climate action. She said that their work had underpinned the delivery, during the Gillard Government, of a clean energy bills package which addressed every aspect of climate change.

Hollo is also proud introducing the global movement, Buy Nothing, to Canberra. By 2020, there were 28 Buy Nothing groups (29 if you count Queanbeyan) across the ACT, more than in Sydney. That Canberra, the bush capital is a “green” city, is also reflected in the results of the 2020 ACT elections which saw six Greens members elected to the ACT Legislative Assembly and becoming a third force in ACT politics.

Hollo is a true Renaissance man: academic, activist, author, entrepreneur, environmentalist, essayist, lawyer, musician, singer, and writer. He also claims to have “read everything” ever written by ground-breaking American author, Ursula K. Le Guin, including her novels, short stories, and poetry.

Like words and the environment, music is one of Hollo’s “first and great loves”. It always has been a crucial part of his life. When Hollo is stressed or tired, he “listens to beautiful music or goes for a walk in nature, or both”.

In 1995, at university, Hollo founded the four-piece indie rock band, FourPlay String Quartet, with his brother Peter. Although he didn’t know Hollo at the time, Braddock recalls buying FourPlay’s first album, Catgut Ya Tongue? in the late 1990s. “It was excellent, I loved it”, Braddock says.

No one is safe until we’re all safe

After music, which Hollo studied at high school on a scholarship, and later at university, Hollo found the law. While never wanting to be a lawyer, Hollo was always interested in policy, social change, and how “the legal system manages our society for good and ill”. Hollo considered the law was a key vehicle to understand how the world, and the rules of the world, work.

Towards the end of his law degree, Hollo studied both environmental law and international humanitarian law (and how that can regulate the environmental impact of war). He sees “war as one of the gravest of evils, driven by greed, and usually by men in power”.

Hollo is appalled by the situation in the Ukraine. He believes it is “absolutely devastating, whether or not you have family there”.

Although Hollo has never been to the Ukraine, he feels personally connected because he grew up listening to his grandmother’s stories about Odessa. Family is central to Hollo’s identity. He has been a stay-at-home-dad for his two children, and the stories of his parents and grandparents, who were refugees, are very much part of what has made Hollo the person he is.

Hollo’s Jewish grandparents taught Hollo that “it is the responsibility of those with privilege to ensure the safety of others … no one is safe until we all are … everyone’s decent life is contingent on everyone else’s”.

Having been enslaved and become free, his grandparents believed it was very much their responsibility to “do the right thing” by others who are enslaved, or otherwise in harm’s way.

On 2 May, the roadside signs of Professor Kim Rubenstein, who is running as an Independent for the Senate in Canberra, were defaced with “disgusting anti-Semitic” words and images .Hollo, who is Jewish but not religious, was quick to condemn those responsible. “We need to stand together saying there should be no place for hatred in politics,” Hollo wrote.

When he ran for office in 2019, English-born Hollo needed to explore his heritage and investigate the renunciation of seven possible citizenships to ensure his eligibility to represent Australia as a politician.

Having sorted that out, in line with his grandparents’ philosophy, Hollo has further honed his commitment to making Australia, and the world, environmentally and democratically safe.

While keen to tackle climate change, Hollo also wants to tackle corruption. He wants to make the Australian government properly accountable, including through the establishment of an “anti-corruption body with teeth” and the powers of a royal commission.

Hollo also wants to see a ban or limit on political donations from big corporations so that their power and control over the writing of government policy, regulation, and legislation is weakened.

The manipulation of the political system through “old boys clubs” and the “revolving doors between political and corporate offices, particularly in fossil fuel corporations has to change. It represents a threat to our democracy”.

Hollo says it is increasingly difficult to call the current governance arrangements in Australia democratic. “We are on the way to becoming a kleptocracy, or an oligarchy,” he says. Or in the words of former Australian Greens Senator, Scott Ludlam, “to state capture”.

He says we are “pretty thoroughly controlled by corporations and that makes political change well nigh impossible … and this is absolutely at the core of what we need to address”.

On 2 May, off on his “pushie” to yet another campaign event, his bike weighed down on the left with campaign signs, Hollo cheekily tweeted: “Environmentally friendly and heavy on the left, that’s what you get from the Greens.”

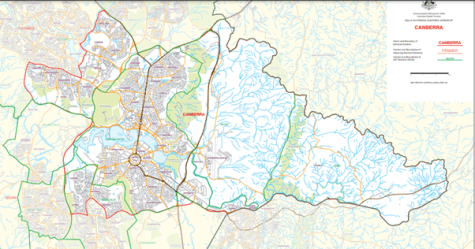

The seat of Canberra, which Hollo is contesting, looks like a giant foot. Australia’s Parliament House, sitting on Capital Hill, is located by the ankle of that foot. Together, Hollo and The Greens are taking firm aim at the Coalition’s Achilles’ heel.

They plan to use the foot to help kick the Coalition out of office, to bolster The Greens’ status as a third force in Australian politics, and to ensure that, in the process, Australia’s governance becomes more democratic, transparent, and accountable.

Braddock said that if elected, Hollo would bring his “values into the Parliament so when it comes to a debate on an integrity commission or on action on climate change, he is someone who will listen to those values and get them into the legislation”.

Hollo is bent on cleaning-up the joint. One might say he wants to “Green-up to Clean-up”, not only Australia’s natural environment, but also the growing corruption of its corporate and political environment.

Allison Ballard is a member of the ACT Greens